silent night [puts & campbell]

[10/2012] | [winner, 2013 opera america director-designer showcase]

composer | KEVIN PUTS

librettist | MARK CAMPBELL

designer | MARIANNA CSASZAR

lighting designer | SARAH HUGHEY

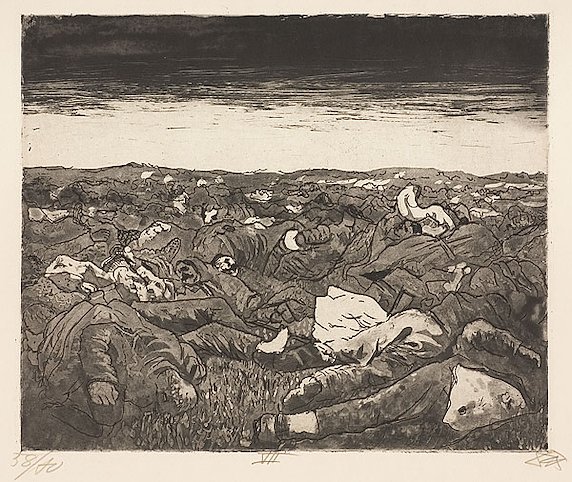

A key research image in this design process was this drawing by Otto Dix, which shows the casualties of war as the landscape itself. This eminent artist who, as a WWI soldier, was a first-hand reporter of the experience of war.

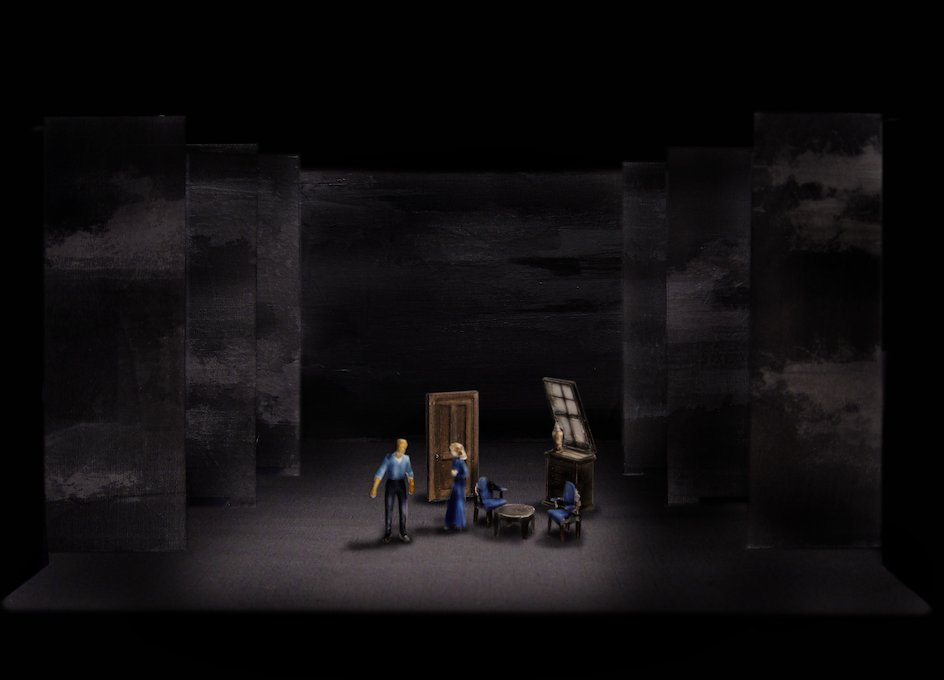

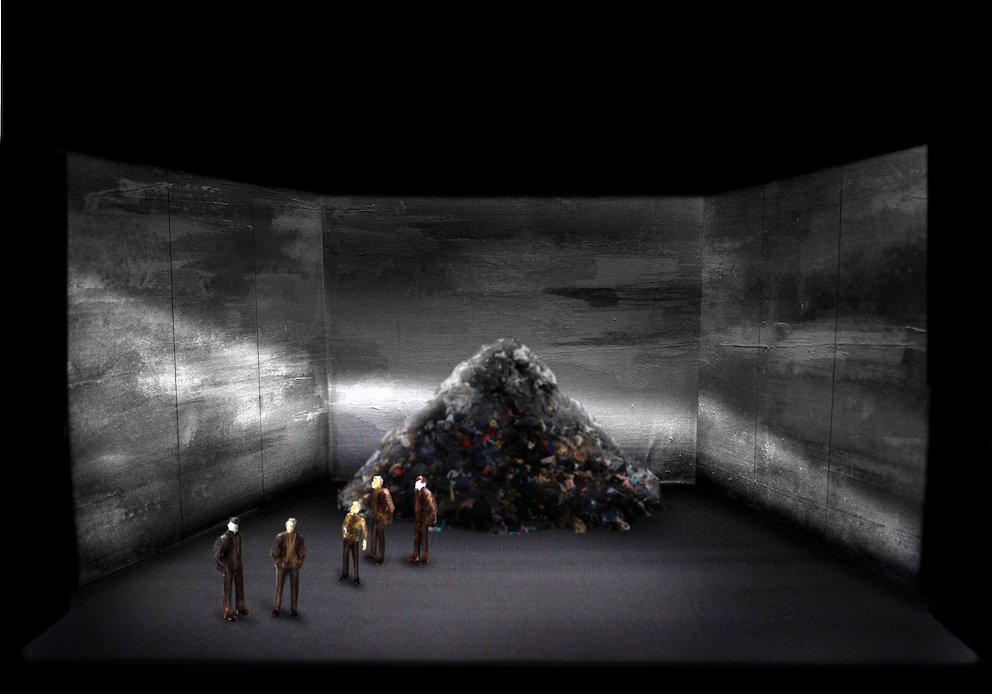

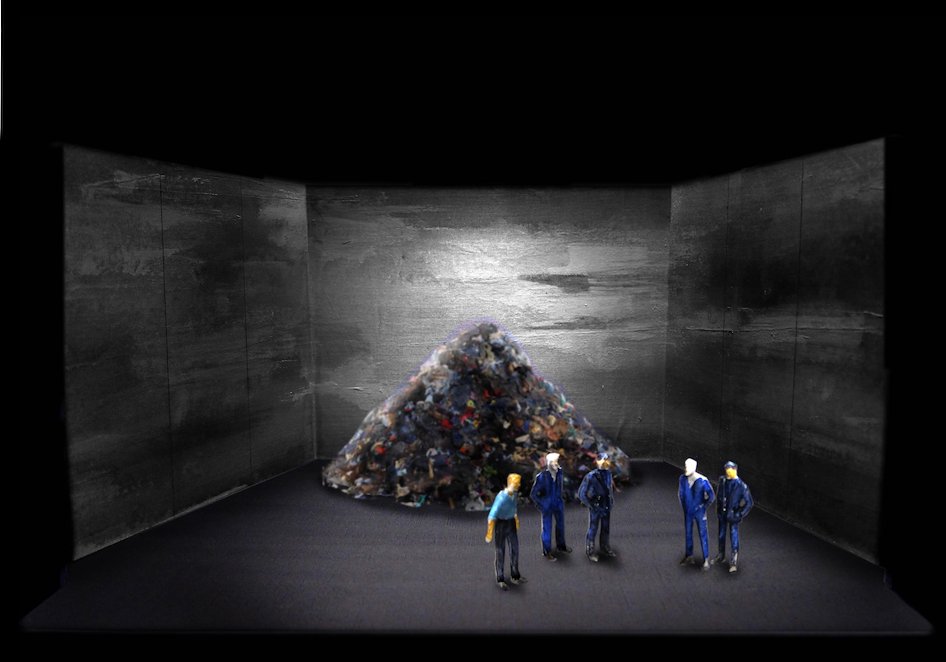

The costume design is historically accurate, taken from the period of WWI. The soldiers’ uniforms are color-coded, taking colors from recruitment posters: the French in blue, the Germans in red and grey, and the Scots in brown.

These colors are also used in the civilian clothes that appear in the production: the blue of the French in Madeline’s dress, the German red in Anna’s costume when she’s playing a stage character and the brown of the Scotsmens’ wool suits worn prior to their enlistment.

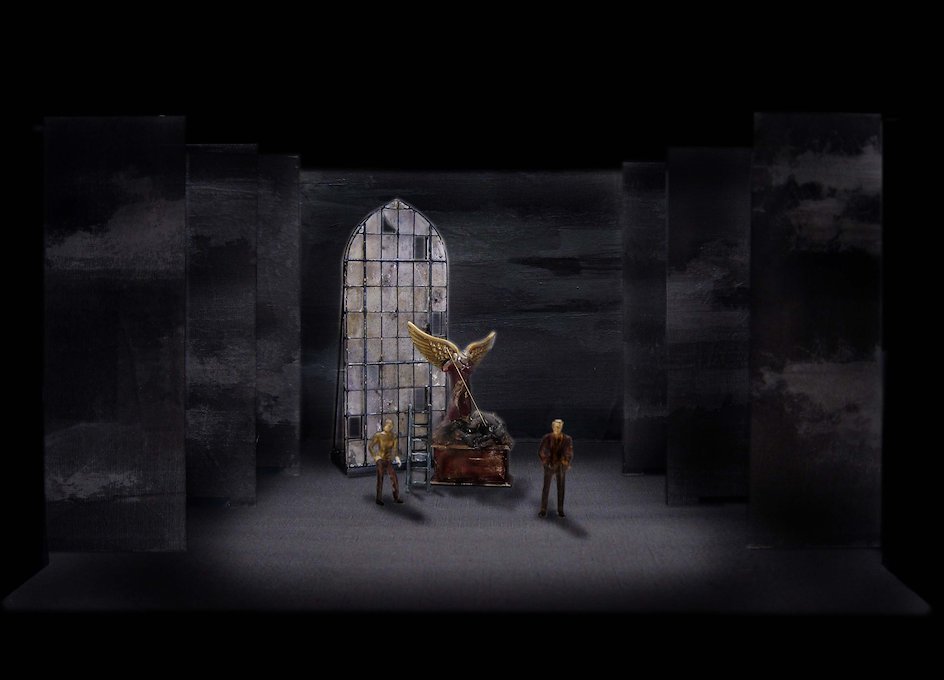

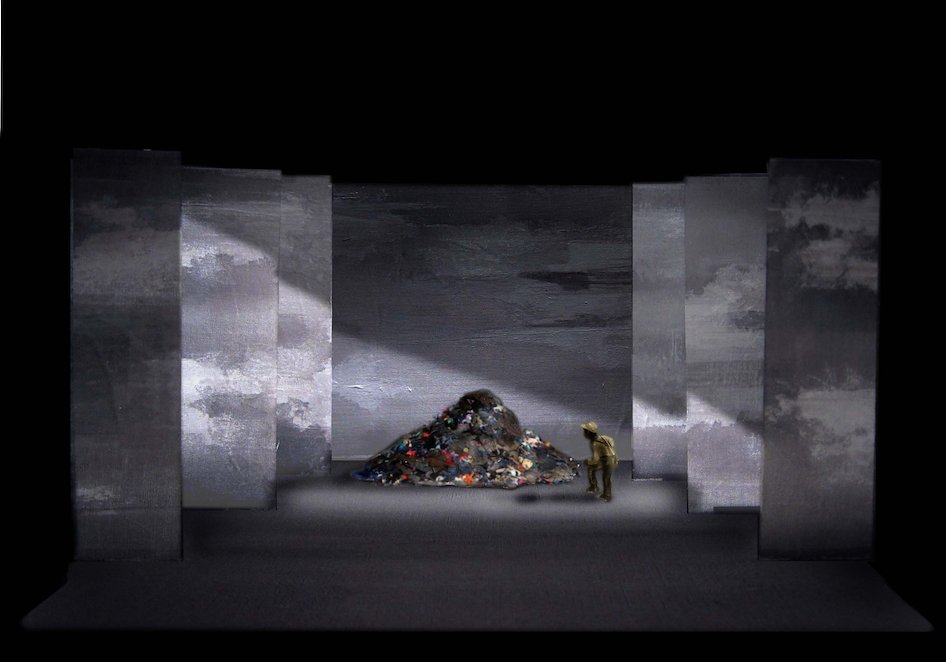

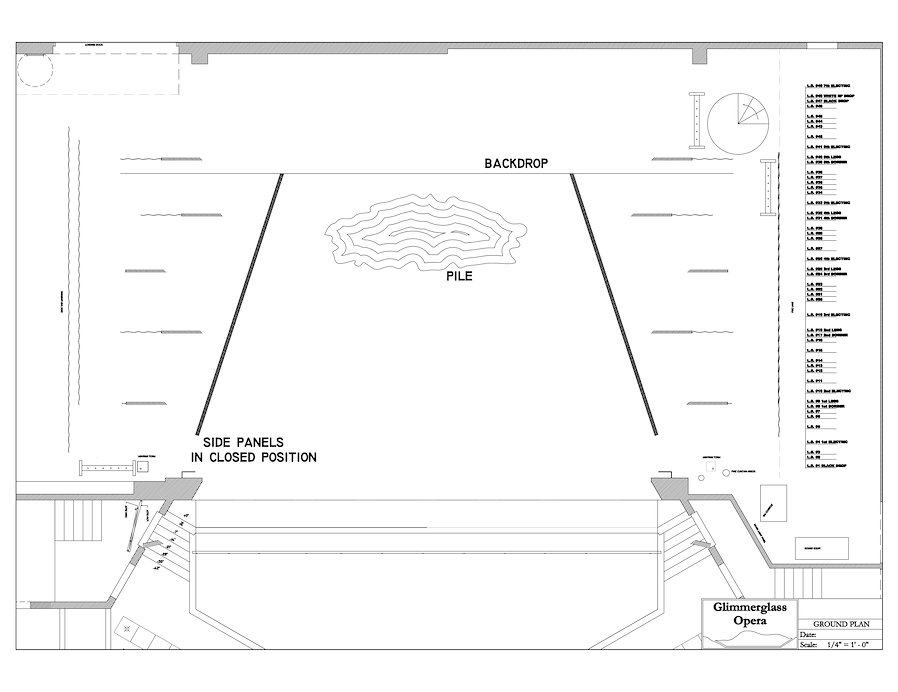

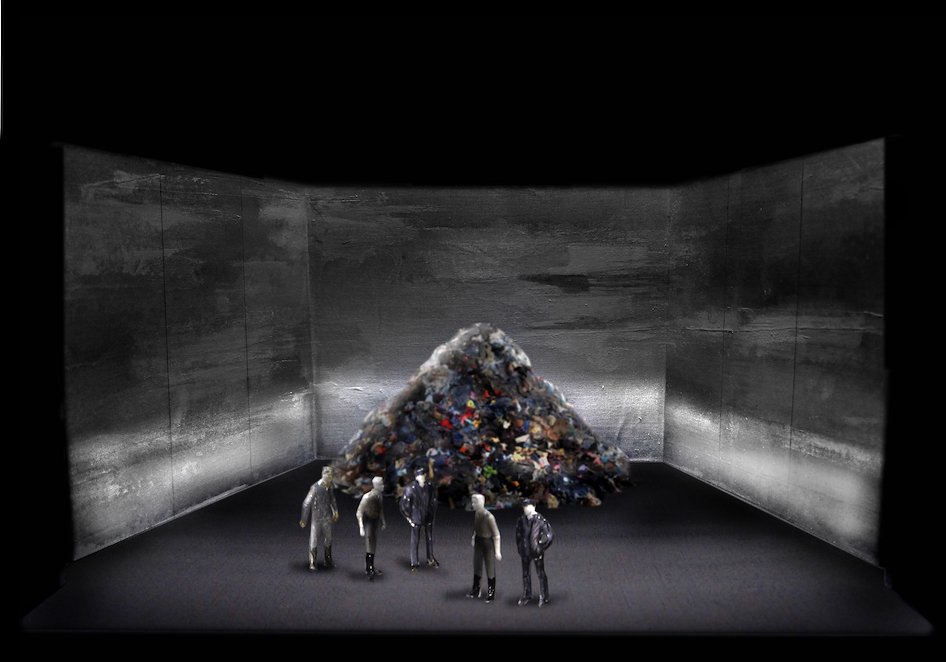

The scenic design was inspired by the work of Christian Boltanski, a contemporary installation artist whose work addresses the emotional aftermath of military conflict. This led us to a single, simple gesture: a mound of bloodied, distressed uniforms, helmets and boots.

The opening to SILENT NIGHT shows the three central protagonists leaving their peacetime lives and preparing for war: Nikolaus as an opera singer in Germany...

...Jonathan as a church acolyte in Scotland...

...and Audebert as a father-to-be in France.

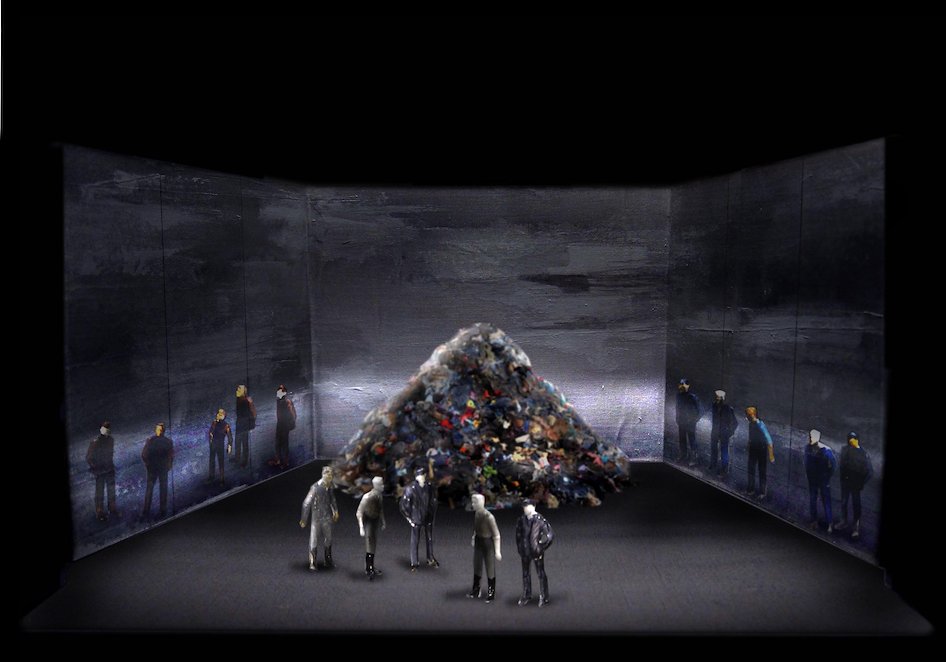

When the opera is interrupted by the announcement that war has been declared, we hear the chorus begin to sing a German war song. These choristers, in uniform, are slowly revealed in silhouette behind scrim panels at stage left and stage right. These panels are a key part of the overall design palette and their ability to create silhouette is used in other ways in the production. The overlapping images of opera singers and soldiers create an atmosphere of terror, pressure and suffocation, a feeling that is found later in the Trenches.

With the beginning of the discordant battle music, soldiers run onstage from the wings, adding debris to the central pile. This music is marked “apocalyptic” in the score, which supports a sudden, dynamic shift in staging, together with the solitary pile.

First the French and Scots run on from stage left; then the Germans retaliate from stage right.

During these five minutes of music, more clothes are added to the pile by the soldiers through a choreographed sequence of back and forth movement.

At the end of the music, William is shot and dies in Jonathan’s arms. The pile is complete and the panels close, sealing the space and suggesting the feeling of pressure and entrapment of the soldiers in their respective trenches.

In the trenches, the enemy remains unknown, hidden, and terrifying. The audience doesn’t get access to all three trenches at once, but rather, the entire stage space represents the trenches. This concept recreates the emotional experience of being in the trenches, rather than the physical one.

As the entire stage represents the trenches, shifts in the shape, shadow, angle and intensity of the lighting further clarify which trench we are in: Scots, French or German. The landscape is devoid of color, as if the war has bled all life, and with it, color, out of the vista. Here is the Scots trench, with light coming from the high stage right side...

...the French location uses light from directly above...

...and the German trench from the low sides.

However, the scrim panels allow us to see the soldiers of the other armies in silhouette. This creates the atmosphere of fear and terror seen earlier in the Prologue when the soldiers prepare for war. These men survive in the Trenches under the ever-present threat of death. There are always other men out there wanting to kill you.

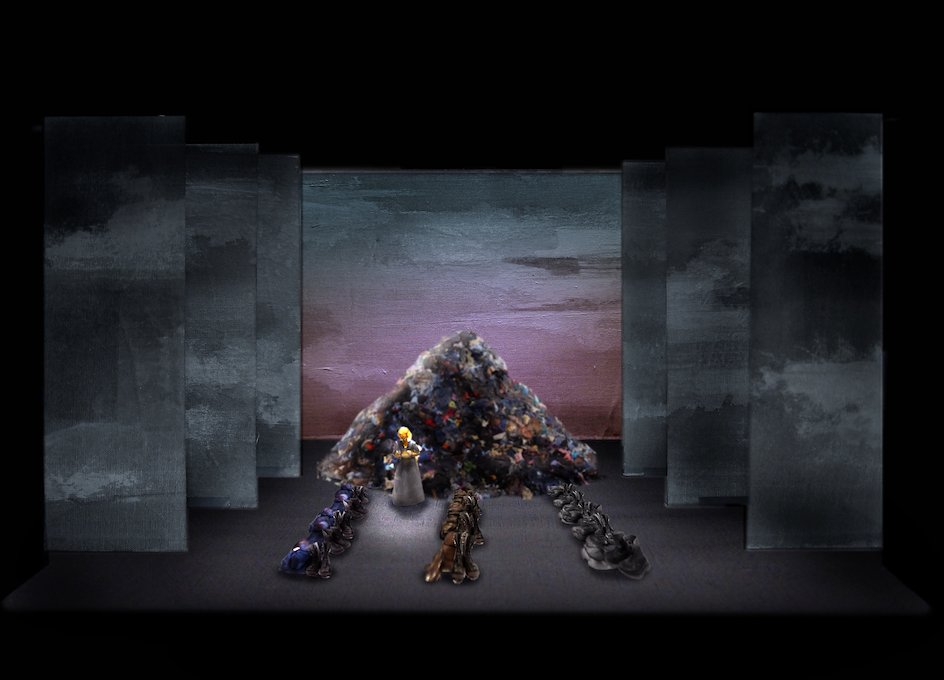

The event of the Truce takes place in No Man’s Land, between the Trenches. Having climbed on top of the central pile, Nikolaus sings a Christmas song. The side panels open for the first time since the Battle at the beginning of Act One, and soldiers creep in cautiously from all sides. Color is also added into the lighting design for the first time. Up to this point, the scenic color palette has been entirely in grayscale, but with the truce and the hope for peace comes the amber color of the evening sky.

Anna, Nikolaus’s lover, sings movingly about the horrors of war and its effect on the women left behind: the wives, the mothers, the daughters. The marking here is “with quiet nobility, like a funeral march.” As Anna sings and the sun rises, the men slowly begin to dismantle the central pile, ceremoniously folding the clothes and making smaller piles of uniforms, boots and helmets.

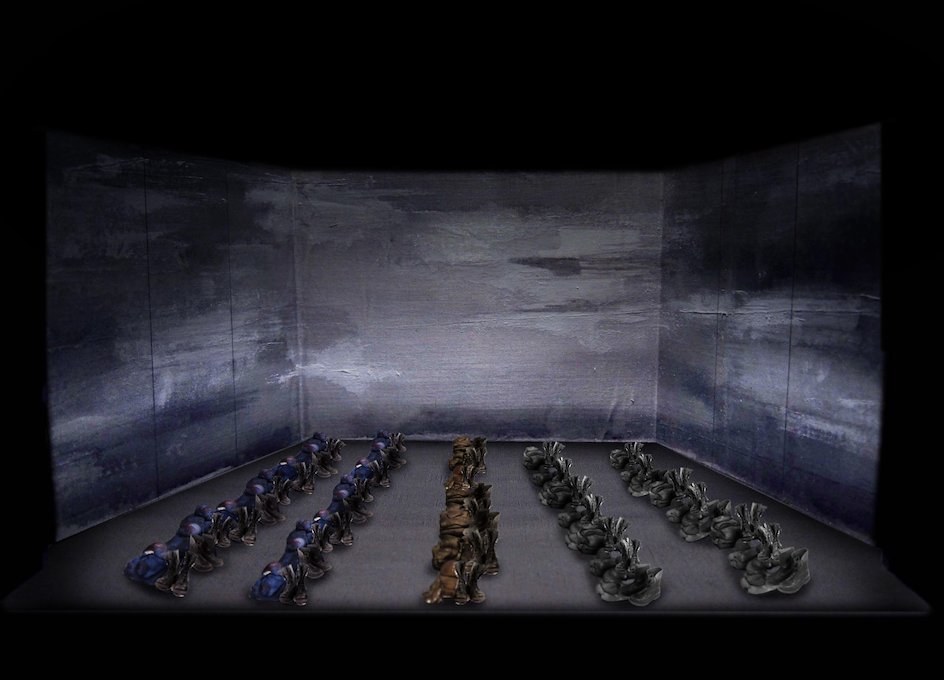

In the opera's final scene, the burial is complete. We are left with a grid of small piles, suggesting tombstones in a graveyard, against the same monochromatic backdrop from the Trenches. The soldiers, having been shipped off to other battlefields by the Generals, exit by marching through the open panels which close behind them. As the closing bars of the music fade to silence, we simply sit in that silence, in the graveyard, in the fading light, with the memories of those we’ve lost forever.